How to import the World. And why it’s so hard.

I share why importing and modeling geo data is one of the hardest parts of building a travel platform. From cities and neighborhoods to fragmented providers, polygons, and performance trade-offs.

I thought I just needed cities and countries. Then came neighborhoods. Then multiple languages. Then accommodations and tours. Then five providers.

Then everything broke.

This is the point where you realize you’re no longer building search — you’re trying to model reality.

If you operate a travel platform that lets users search for stays, tours, or transportation for their next trip, one thing becomes obvious very quickly:

you’re not just building search — you’re modeling the world.

To make sense of where accommodations, tours, and destinations belong, you need a solid geographic foundation that represents how places relate to each other. Countries contain regions, regions contain cities, cities contain neighborhoods, and real-world places rarely fit nicely into clean boxes.

At first glance, this sounds like a solved problem. Surely there must be a go-to solution — Google Maps, Google Places, Mapbox, something like that.

That assumption holds exactly until you stop pointing at places and start trying to understand them.

And for simple use cases, that’s true.

If all you need is a search box that turns “Barcelona” into GPS coordinates and finds nearby hotels, using a paid API works just fine. The pay-as-you-go pricing model is reasonable as long as traffic and conversions are in balance.

But once you want to understand a destination — not just point to it — things start to get complicated.

A real-world example

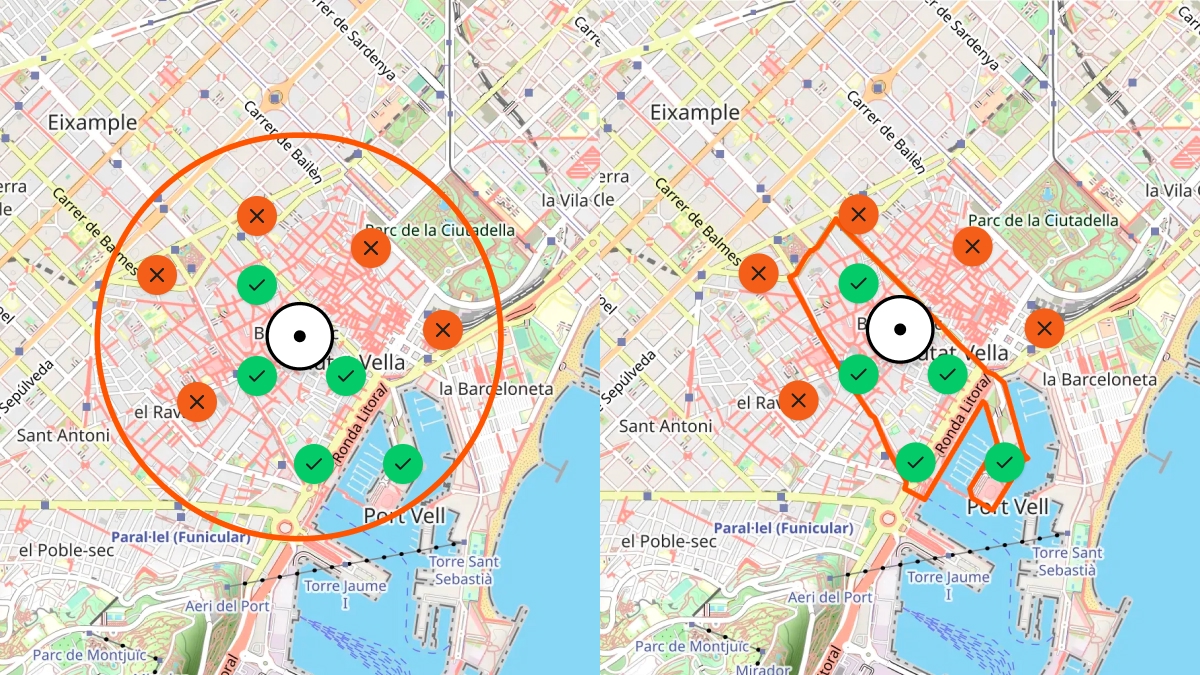

Imagine you want to truly model a destination like Barcelona.

Not just the city itself, but:

- its neighborhoods,

- the attractions inside those neighborhoods,

- and which areas are most popular or characteristic.

Let’s say you already have a list of neighborhood names.

Here’s what happens next:

- You resolve each neighborhood name via the Google Geocoding API to get GPS coordinates so you can display it on a map.

- You then use the Google Places API to find attractions or points of interest within a radius around each neighborhood.

So far, so good.

This is the moment when “just use Google” quietly stops being an option.

Now comes the catch.

The moment you want to store that data in your own database, you hit a legal wall:

Google does not allow you to permanently store resolved GPS coordinates from their APIs.

You’re only allowed to store the Place ID.

Every time you want to render that place on a map again, you have to:

- call Google’s API,

- resolve the Place ID back to coordinates,

- and pay for it again.

Now imagine doing this:

- for hundreds of cities,

- thousands of neighborhoods,

- and millions of places worldwide.

Costs add up quickly — and worse, you still don’t actually own the data. You can’t run complex analysis on it or model relationships freely.

How I solved this in the past

I’ve run into this problem multiple times over the last 10+ years building travel tech.

The most reliable way to regain control over geographic data is to start with open datasets — most notably geonames.org.

Geonames.org provides structured data for:

- countries,

- regions,

- cities,

- neighborhoods,

- airports,

- train stations,

- and other geographic entities.

Each entry comes with latitude and longitude, translated names, and references to parent entities.

Sounds simple — but importing this dataset properly is already a challenge.

You need:

- efficient indexing,

- fast spatial queries,

- and a schema that works at global scale.

I’ve built this pipeline several times and was able to reuse large parts of it. The result: eliminating hundreds of euros per month in API costs and replacing them with a self-hosted solution that costs only a few dollars.

But saving money was just the side effect — the real win was finally owning the data.

Building a better Travel Experience with Data

For my startup Planaway, I wanted to go further than reusing old code.

I strongly believe that a travel platform should understand destinations — not just list products inside them. If a system truly knows how places relate to each other, it can:

- provide better context to users,

- create more meaningful groupings of tours and stays,

- and offer smarter recommendations.

I don’t just want to know whether a hotel is “near” a neighborhood.

I want to know whether it’s inside that neighborhood — or across the river on the other side of the city.

Users should see destinations highlighted precisely on a map, following real borders instead of rough circles.

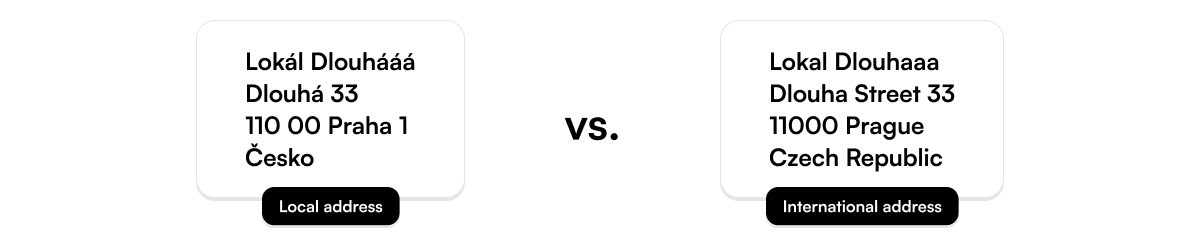

And there’s another subtle but important detail:

addresses are not just coordinates.

A traveler might see an English-localized address, but locals use the native version. Supporting native street names, characters, and formats enables travelers to communicate naturally with people on the ground.

All of this requires building — and owning — your own geo-spatial dataset.

Fragmented data becomes your enemy

Once you own a geo-spatial foundation, every tour, accommodation, or transport option has to attach itself to a specific place in that system.

This is where most travel platforms slowly lose control of their own system.

At that point, the hardest part begins:

Importing spatial and descriptive data from many external providers and turning it into a unified, searchable system.

In travel, there are hundreds (if not thousands) of APIs:

- flights,

- accommodations,

- tours,

- transfers,

- events,

- rental cars.

Each provider:

- exposes a different API style,

- uses different schemas,

- and often delivers incomplete or inconsistent geo data.

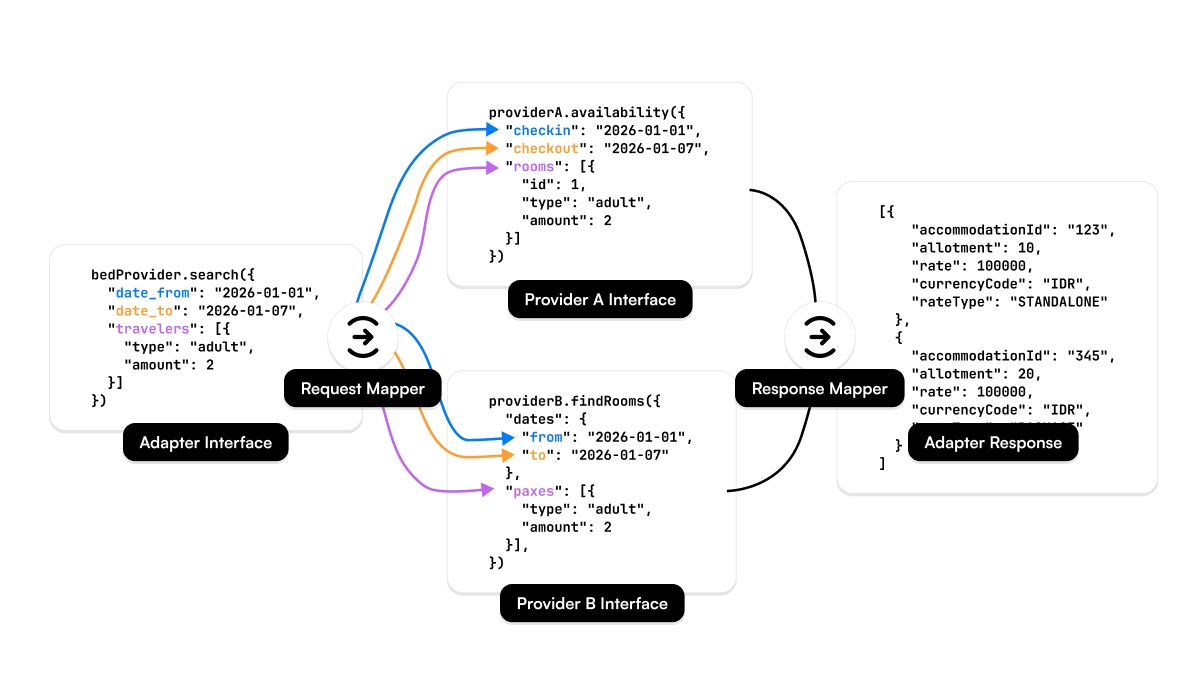

The diagram above shows how data flows through Planaway’s system before it ends up in our databases.

Let’s break it down.

Layer 1: External data sources

Each provider focuses on their own domain and optimizes for their own needs. Some return full addresses, others only city names. Some provide polygons, others just a single coordinate.

None of them agree.

Layer 2: Universal Adapter (Typescript Package)

To deal with this, I introduced a set of universal adapters per domain:

- Geo Adapter

- Tour Adapter

- Bed Adapter

- Air Adapter

- Move Adapter

Each adapter defines a strict internal schema and uses mapper classes to transform provider-specific data into that schema.

These adapters live in isolated TypeScript packages, decoupled from the core system. This forces clean abstractions and makes sure new providers don’t slowly corrupt the data model.

Layer 3: Content importer service

The content importer orchestrates everything:

- scheduled updates,

- retries,

- checksums for data integrity,

- and cleanup of outdated data.

It runs 24/7 on a queue-based system using Redis, with multiple worker nodes processing imports in parallel.

One key feature is data reduction.

A full accommodation dataset might be tens of gigabytes stored in S3 — but for search, we only need a tiny subset. We compress full documents into minimal search documents.

For example:

- ~2 million accommodations

- ~50 GB raw data

- ~150 MB searchable index

That difference alone can mean hundreds or thousands of euros per month in infrastructure costs.

Layer 4: Data storage layer

We persist data across:

- PostgreSQL (relational),

- MongoDB (document store),

- AWS S3 (object storage).

This diagram focuses on geo-spatial data only.

Descriptive content like images, localized text, or amenities lives in S3. That might sound odd, but it’s cheap, fast, CDN-cacheable, and we never run complex queries on it. Why force everything into a database just because it “feels right”?

At this scale, pragmatism beats ideology.

Special case: geo-spatial polygons

Polygons look innocent — until they turn every search into a performance problem.

A polygon defines an area using many latitude/longitude points. The more points it has, the more accurate it is — and the slower spatial queries become.

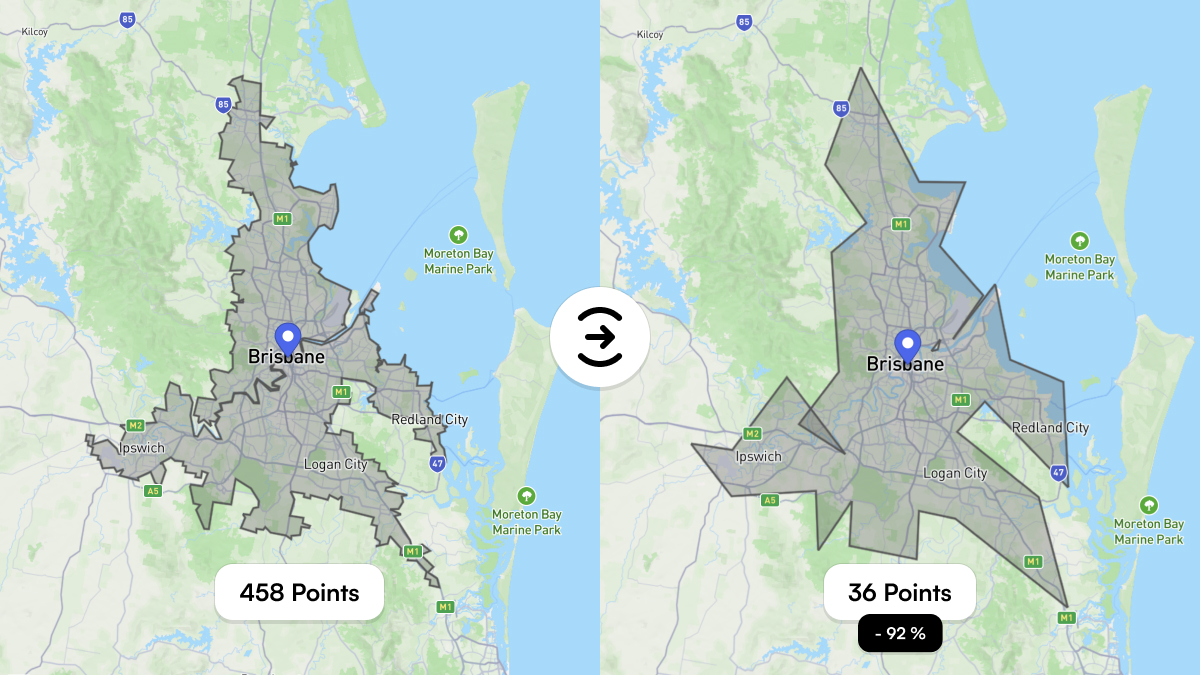

Brisbane’s city polygon has 458 points.

Every spatial query has to evaluate those points against millions of documents.

That’s expensive.

The solution: polygon simplification.

By reducing polygons to visually equivalent shapes with ~90% fewer points, we dramatically reduce computation time without affecting user experience.

Brisbane’s polygon can be reduced to 36 points, cutting query cost by ~92%.

Wrap-up

Building a geo-spatial foundation for a travel platform isn’t about maps. It’s about modeling reality — and reality is messy.

Cities overlap, names change by language, providers disagree, and nothing fits neatly into a single database.

This post was a glimpse into the challenges of importing and structuring the world for Planaway — and for any system that wants to reason about real-world locations.

Next, I’ll explore Uber’s H3 system and how hexagonal indexing can eliminate many geo-spatial queries entirely by turning geography into simple string lookups.

I intentionally kept this post accessible, while still going deep enough for technical readers. If you’re building something similar — travel, logistics, real estate, or marketplaces — you’ll likely run into the same problems sooner than you expect.

Pros and Cons at a Glance

If you’ve read this far and just want a compact comparison, this table summarizes the trade-offs between relying on external geo APIs and building an own hosted geo dataset. Neither approach is inherently right or wrong — but they optimize for very different things. The moment you move from “finding places” to actually understanding them, these differences start to matter.

| Aspect | External Services (Google Places / Maps, Mapbox) | Own Hosted Geo Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Getting started | Very fast. Minimal setup, great docs, instant results. | High upfront effort. Data import, modeling, indexing required. |

| Data ownership | You don’t own the data. Storage and usage are restricted by license terms. | Full ownership. You control how long and how deeply data is stored. |

| Storing coordinates | Often restricted. GPS coordinates usually can’t be stored permanently. | No restrictions. Coordinates, polygons, and metadata can be stored freely. |

| Cost model | Pay per request. Costs scale with traffic, not with business value. | Fixed infrastructure cost. Scales with data size, not query count. |

| Global coverage | Excellent, but abstracted. Limited insight into how places are modeled. | Depends on dataset quality. Full transparency into structure and hierarchy. |

| Neighborhoods & regions | Inconsistent. Often approximated or radius-based. | Precise. Supports real boundaries using polygons. |

| Multilingual names | Localized, but often lossy or normalized. | Native and localized names can coexist without loss. |

| Address formats | Standardized, sometimes anglicized. | Native address formats preserved alongside localized versions. |

| Complex analysis | Limited. Mostly lookup-based. | Full freedom. Aggregations, clustering, custom logic possible. |

| Performance tuning | Black box. You adapt to the API. | Fully controllable. Indexing, caching, simplification strategies. |

| Vendor lock-in | High. Switching later is expensive. | Low. Data and schemas stay under your control. |

| Long-term scalability | Expensive at scale. Cost grows with every search. | Predictable. Cost grows slowly with data volume. |

Share your thoughts with me! They will not be published.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter to get notified about new posts and other updates.

No Spam — just ideas, insights, and maybe a rare bug turned life lesson.